Complementary and Alternative Medicine for treating Low Back Pain with Teaching Exercise: A narrative review

Article information

Abstract

Objectives

In modern society, many people have low back pain (LBP) and spinal diseases. About 80% of them experience severe LBP more than once in their lifetime. We can find studies on many Korean medicine-based treatments, such as acupuncture treatment for LBP and exercise therapy, which are effective in reducing the symptoms. This study focuses on the combined effect of both Korean medicine and exercise therapy for treating LBP.

Method

For this review, we searched for articles focusing on pain and disability recovery in pre-clinical and clinical studies of extension and flexion exercise therapy related to LBP.

The search databases were as follows: PubMed, Google Scholar, and seven Korean electronic databases (Korea Citation Index (KCI), Korean studies Information Service System (KISS), Research Information Service System (RISS), Oriental Medicine Advanced Searching Integrated System (OASIS), DBPIA, National Digital Science Library (NDSL), and KOREAMED). The keywords were as follows: Korean Medicine, back pain, flexion exercise, extension exercise, McKenzie method, McKenzie exercise, Williams’ flexion exercise, and Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy.

Results & Conclusions

This review shows the usefulness of flexion and extension exercises for LBP treatment and effective patient education, but further studies are necessary.

Introduction

In modern society, several people have low back pain (LBP) and spinal diseases. About 80% of them experience severe LBP more than once in their life time; it is the second most common disease in adults under the age of 45 years, the first being a cold.1)

Low back pain can lead to secondary diseases by lowering the quality of life and limiting exercise and daily activities.2) Various treatment modalities for lumbar and spinal diseases exist in both Western and Korean medicine, and a medical approach appropriate for each disease is required.3)

The diagnostic classification of low back pain is as follows: Specific spinal pathology, Nerve root pain/radicular pain, and Non-specific low back pain.4) Among these, in the case of non-specific low back pain, ‘Red flags; There is no fracture, tumour, infections, systemic inflammatory disease’ and is not a Radicular Syndrome.5)

In addition, low back pain is divided into Acute (for less than 4 weeks), Subacute (for 4–12 weeks), and Chronic (for more than 12 weeks), based on the onset and duration, according to the ACP Guideline.6) According to the NASS standards, low back pain is divided into Acute (for less than 6 weeks), Subacute for (6 to 12 weeks), and Chronic (for more than 12 weeks).7)

Various treatments are performed for patients with chronic low back pain (C-LBP). However, when previous treatments are not effective, patients eventually visit the Korean medical clinic. According to the National Statistical Office (NSO), among the reasons for outpatient treatment in Korean medical clinics in 2014, low back pain accounted for 17.77%, which was the highest rate of use among single diseases, excluding other classifications.8) Studies have shown that practitioners tend to choose therapies such as acupuncture, Korean medicine physical therapy, moxibustion, cupping, use of a pack of prepared herbal medicine, Chuna manual therapy, herbal decoction, and pharmacopuncture, in this order.9)

The effectiveness of acupuncture for LBP has already been proved, and even in the guidelines6, 7,10) for LBP published in Europe and the United States, acupuncture (acupuncture treatment, laser acupuncture) is a Grade-A recommendation for C-LBP.

Exercise therapy for LBP can be broadly divided into extension exercises and flexion exercises. The representative exercise for extension is the ‘McKenzie Method’, and the flexion counterpart is ‘Williams Flexion exercise’. Our aim was to check the actual effectiveness of exercise therapy that can enhance the effectiveness of Korean medicine treatment for low back pain. In addition, a summary of the exercises, which are actually applicable to patients receiving Korean medicine treatment has been included.

Methods

For this review, we searched the existing literature focusing on clinical studies depicting the effect of exercise on LBP. The search keywords included Korean Medicine, LBP, Flexion exercise, Extension exercise, McKenzie method, Williams’ flexion exercise, and Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy, and the following databases were searched: PubMed, Google Scholar electronic databases, Korea Citation Index (KCI), Korean Studies Information Service System (KISS), Research Information Service System (RISS), Oriental Medicine Advanced Searching Integrated System (OASIS), DBPIA, National Digital Science Library (NDSL), and KOREAMED.

Use of exercise for treating LBP

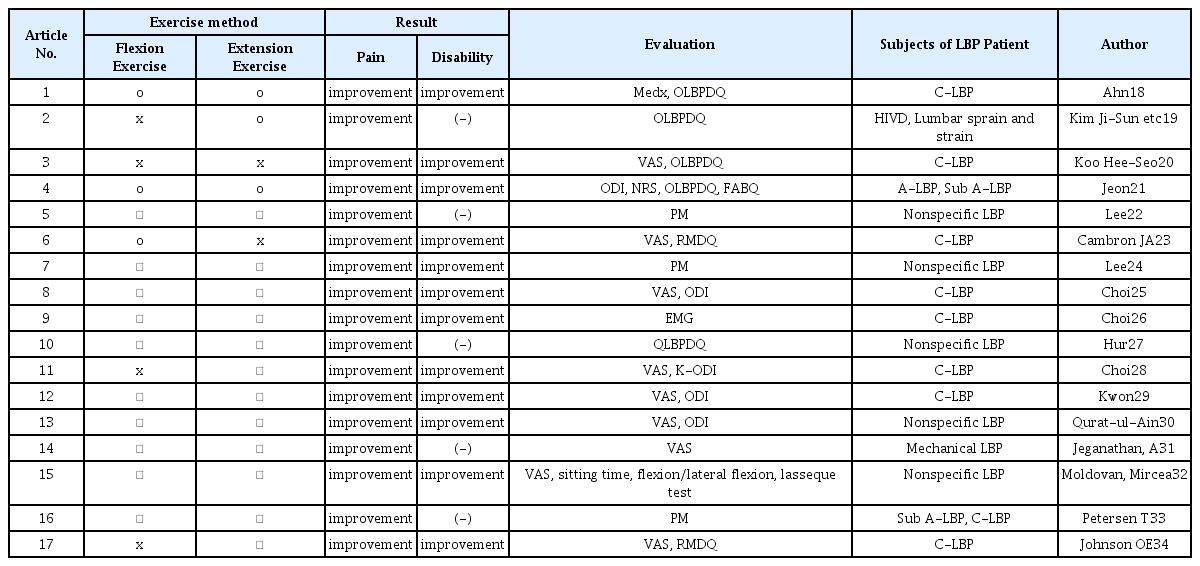

The summary of the details of exercises used for treating LBP are shown in Table 1.

1. Flexion exercise for LBP: Williams flexion exercises

Williams’ exercises (Williams’ lumbar flexion exercises, lumbar flexion exercises) mainly use flexion for exercise therapy. This method was first proposed by Paul C. Williams in 1937. Williams thought that LBP is caused by the compression of the intervertebral discs due to incorrect posture, which is the result of a lack of flexion exercises in daily lives.

The Williams flexion exercise consists of 7 types of exercises (pelvic tilt exercises, partial sit-ups, single and bilateral knee-to-chest, hamstring stretching, standing lunges, seated trunk flexion, and full squats), through which it improves lumbar flexion and strengthens the gluteal and abdominal muscles to recover from LBP.11) In fact, one study showed increased flexibility in the hamstrings, gluteal flexors, and lumbar extensors and decreased LBP.12)

2. Extension exercise for LBP: McKenzie Method

In exercise therapy, the representative method of extension exercise is the McKenzie exercise. The McKenzie exercise is a workout method proposed by Robin McKenzie, a physical therapist in New Zealand. It categorizes LBP into three mechanical syndromes (posture, function, and regression) and other diseases (spinal stenosis, hip pain, sacroiliac joint pain, mechanically inconclusive diseases, spondylolisthesis, and chronic pain), and proceeds with a suitable exercise method.13) McKenzie believed that a slouching posture usually moves the disc nucleus backwards, causing LBP. He aimed to increase the strength of the extensors in the lower back. There is a theoretical basis for pain relief upon moving the intervertebral disc forward through the extension of the lower back.14)

McKenzie’s exercise therapy is classified into three mechanical syndromes through mechanical loading strategies (MLS), which are evaluated using the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) for pain at the base point, pain at the extension point, and pain after extension. McKenzie suggested 25 exercises to treat LBP, based on MLS. Most exercises focus on extension, but flexion exercises are also performed as needed.15) Several studies have shown that McKenzie’s exercise therapy improves LBP, especially Acute LBP.16,17)

Summary of the effects of exercise treatment on LBP

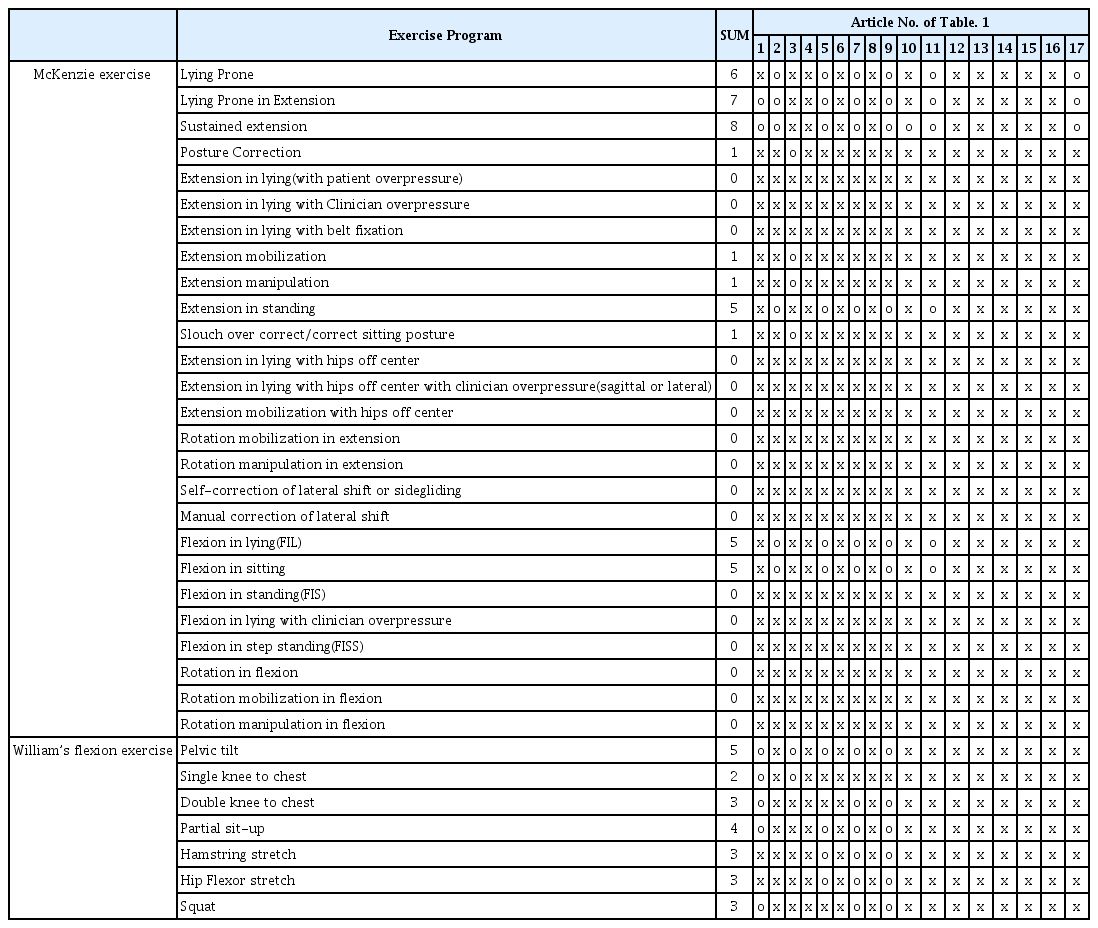

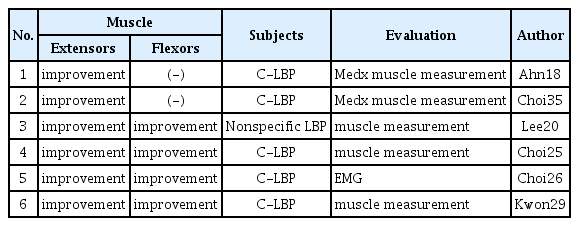

This review summarizes the effects of exercise, including flexion and extension exercises, in patients with low back pain (Table 1, Table 2). In addition to McKenzie’s and Williams’ exercise therapy, all similar exercises are classified according to pain, disability, and muscle strength. The actual methods used for the McKenzie and Williams exercise therapies in each study are summarized in Table 3.

Effects of Flexion and Extension Exercise on LBP patients: Focusing on Extensors and Flexors improvement

A summary of the studies on each exercise therapy showed that both the pain and disability levels decreased. It was more important to perform one of the exercises than to have the flexion and extension movements. Various exercises using both the flexors and extensors reduced pain and disability.

Some studies state that the McKenzie method is excellent (Ahn18), Qurat-ul-Ain et al30), Petersen et al33)), while others state that Williams’ flexion exercise is better (Jeganathan et al31)).

Pain and disability reduction by McKenzie’s and Williams’ exercise therapies could not be evaluated as superior to that by specific exercise therapy. However, Mackenzie’s exercise may be a better choice because both extensors and flexors improve muscle strength.

Moreover, the results of comparing pain and disability reduction between a ‘trained group on exercise therapy’ and a ‘control group’ showed greater pain and disability reduction with training.36)

The summary of McKenzie and Williams’ exercise therapy used in each paper was invalidated if there was no detail, and if the detailed description of the motion was in accordance with each exercise, a point was used to grade each movement. Mackenzie’s exercise therapy included lying prone, lying prone in extensions, sustained extensions, posture correction, extension mobility, extension in a standing position, slouch over correct/correcting, and flexion. Williams’ exercise therapy used pelvic tilt, single knee to chest, double knee to chest, partial sit-up, hamstring stretch, hip flexor stretch, and squat. Exercise methods used at least five times were lying prone, lying prone in extension, sustained extensions, extensions in a standing position, flexion in lying (FIL), flexion in sitting, and pelvic tilt in Williams’ exercise treatment (Table 3).

An effective method for treating diseases through a combination of exercise therapy and acupuncture has existed in Korean medicine as Dong-gi acupuncture (DGA), a kind of Dong-si acupuncture. The validity of using DGA for LBP by blood stasis and sprain has also been revealed. In particular, active DGA was more effective than passive DGA or common treatment.37) Another study compared simple acupuncture groups with acupuncture combined with DGA groups for treating cervical spondylosis. The difference in pain relief was not significant with acupuncture, but the time for pain relief was halved when compared with DGA (8.15±2.32 days) or simple acupuncture groups (13.25±4.62 days).38) There was also a study on DGA, which combined flexion and extension exercises for lower lumbar pain. This study combined acupuncture treatment and exercise therapy based on the movement system impairment syndrome (MSIS), and organized the acupuncture points that may affect exercise therapy.39)

LBP is a common condition that affects about 80% of the population at least once in their lifetimes, and Korean medicine treatment, which accounts for about 18% of the outpatient treatment in Korean medicine clinics, is the main treatment.1) Acupuncture is effective for treatment, and this has been demonstrated in guidelines for treatment in the United States and Europe.6,7) Acupuncture-related treatment was recommended as Grade A, and the level of evidence was also observed as Grade Fair. Additionally, acupuncture treatment for C-LBP was evaluated as ‘moderate level’ for the Magnitude of Effect, which is well recognized to signify the level of pain relief; NSAIDs are ‘Small to moderate level’ and Tramadol is ‘Moderate level’. The Non-Specific LBP guidelines are special in that they are also organized cases of better effects when combined with various non-invasive treatments.

By summarizing various studies, we have confirmed that the ‘lying prone, lying prone in extension, sustained extension, extension in standing, flexion in lying (FIL), and flexion in sitting’ of McKenzie’s exercise therapy, and the ‘pelvic tilt’ of Williams’ exercise reduces pain and disability (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3). It has already been confirmed that DGA, a Korean medicine treatment method, combines exercise therapy and acupuncture treatment.

Combining the information mentioned above, we can select an exercise motion within McKenzie’s and Williams’ exercises that is effective instead of utilizing other motions. Acupuncture and exercise therapy can simultaneously be performed at the acupuncture points where exercise is required. With further research, we can expect positive effects of combined acupuncture and exercise therapy rather than a common treatment and a reduction of treatment time for the same effect.

Notes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by clinical research grant from Pusan National University Hospital in 2020.

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.co.kr) for English language editing.