Managing Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Recommendations from the Korean Medicine Mental Health Center

Article information

Abstract

Objectives

The persistence and unpredictability of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and new measures to prevent direct medical intervention (e.g., social distancing and quarantine) have induced various psychological symptoms and disorders that require self-treatment approaches and integrative treatment interventions. To address these issues, the Korean Medicine Mental Health (KMMH) center developed a field manual by reviewing previous literature and preexisting manuals.

Methods

The working group of the KMMH center conducted a keyword search in PubMed in June 2021 using “COVID-19” and “SARS-CoV-2”. Review articles were examined using the following filters: “review,” “systematic review,” and “meta-analysis.” We conducted a narrative review of the retrieved articles and extracted content relevant to previous manuals. We then created a treatment algorithm and recommendations by referring to the results of the review.

Results

During the initial assessment, subjective symptom severity was measured using a numerical rating scale, and patients were classified as low- or moderate-high risk. Moderate-high-risk patients should be classified as having either a psychiatric emergency or significant psychiatric condition. The developed manual presents appropriate psychological support for each group based on the following dominant symptoms: tension, anxiety-dominant, anger-dominant, depression-dominant, and somatization.

Conclusions

We identified the characteristics of mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic and developed a clinical mental health support manual in the field of Korean medicine. When symptoms meet the diagnostic criteria for a mental disorder, doctors of Korean medicine can treat the patients according to the manual for the corresponding disorder.

Introduction

The first case of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in South Korea was reported on January 20, 20201). Initially, the outbreak of the novel coronavirus was expected to be similar to previous epidemics, such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), and was expected to end without a significant impact. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has included several large-scale waves and continues to persist. Although the pandemic appeared to end after vaccines were developed and distributed, it continues to persist owing to the constant mutation of the virus2).

Although the outbreak of an epidemic elevates stress levels across society, most people return to their daily routines without psychological sequelae. For example, a survey conducted two years after the SARS outbreak indicated no significant increase in the prevalence of mental disorders3). However, the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak differs from that of previous epidemics. Compared to other infectious diseases, COVID-19 has spread to more countries, has had a greater impact on daily life, and has had significantly larger financial and occupational impacts4). Additionally, unlike other coronaviruses, COVID-19 exhibits a pattern similar to that of influenza, with a high infection rate, a relatively low fatality rate, and asymptomatic infection5). Furthermore, compared with previous diseases, COVID-19 has infected more people, and a greater number of medical professionals have been exposed to it. Owing to the prolonged duration of the pandemic, its long-term effects remain unknown3). Finally, uncertainty regarding vaccine effectiveness and the possibility of endless social distancing cause considerable psychosocial stress6).

Moreover, COVID-19 has produced social issues, such as social distancing, quarantine, isolation, and financial problems, which can wreak havoc on mental health. In general, the most crucial factors facilitating full recovery after a tragic event are social support and community solidarity. Individuals commonly experience depression and loneliness after a disaster7). In a community with a solid social foundation, a pandemic such as COVID-19 may cause individuals to experience high levels of loneliness 8). On the other hand, a sudden disaster leads individuals to realize their mortality and rely on familiar social support systems (e.g., marriage and religion) to cope with their fear of the unpredictable9). However, social distancing, quarantine, and isolation have rendered these countermeasures unavailable, thereby forcing individuals to independently solve many difficulties and highlight the importance of self-management10).

The current COVID-19 pandemic is affecting the mental health of not only patients, but their neighbors and the general population as well3,11,12). Consequently, unprecedented mental symptoms such as COVID Blue and COVID Red have emerged in public. However, clinicians still diagnose a general psychiatric disorders (e.g., major depression, anxiety disorders, or stress-related disorders) and only categorical treatment is provided for this condition13–16). Increases in the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and anger throughout society continue to affect both primary healthcare and specialized medical institutions. Additionally, the impact of COVID-19 on mental health is often concomitant with emotional, cognitive, and somatic symptoms, such as sleep disorders and fatigue17,18), thus requiring an integrative approach for both the mind and body.

Social policies such as social distancing and quarantine have highlighted the importance of telemedicine and self-management10). The Association of Korean Medicine has consequently established telemedicine centers for confirmed COVID-19 cases19,20). The Korean Medicine Mental Health (KMMH) center developed the “2020 Mind training manual for doctors of Korean medicine at COVID-19 treatment sites” [informally published work] as a reference for doctors providing mental health support at telemedicine centers. The manual was approved for use in the field in the form of telemedicine for patients’ mental health by the Association of Korean Medicine20,21).

The major intervention of the manual was meditation, one of the mind-body modalities. The benefit of meditation on mental health was confirmed by several systematic reviews (e.g., depression22,23), anxiety24,25), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)26), stress27–29), and sleep quality30)). Therefore, meditation was widely recommended in clinical practice guidelines of Korean medicine for mental disorders such as depression31), anxiety disorders including PTSD 32), insomnia33), and Hwabyung (anger syndrome in Korean culture)34). Besides, meditation is essential and basic intervention for survivors of disasters. Thus, it is also recommended in a manual for disaster medical support using Korean medicine for disaster survivors35) and suggested during the COVID-19 pandemic36–38).

As COVID-19 continues to persist for an extended period, individuals who have recovered from COVID-19 and non-confirmed individuals often visit primary clinics with complaints of mental health problems. However, to date, there are no clear guidelines how doctors of Korean medicine provide self-management for mental health to the patients in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, in order to update the previous manual (i.e., 2020 Mind training manual for doctors of Korean medicine at the COVID-19 treatment sites [informally published work]), we narratively reviewed other published review articles and manuals.

Methods

1 Research Team Composition

This manual was developed by researchers at the KMMH center, who previously participated in the development of the “Mind training manual for doctors of Korean medicine at COVID-19 treatment sites” in 202021). Two researchers (SYC and JWK) who participated in the development of the updated manual were professors of neuropsychiatry at Kyung Hee University Korean Medicine Hospital in Gangdong. Moreover, they are members of the Korean Society of Meditation and are R-level meditation instructors. Thus, the Neuropsychiatry Department of the Kyung Hee University Korean Medicine Hospital at Gangdong continues to use mind-body interventions such as mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) and meditation for patients who visit the hospital. To assist in developing the manual, the first author (HWS) participated as a methodologist. To reflect on the medical field, two researchers (SH and HWL) participated as employees of Korean medicine hospitals. On the other hand, to reflect on the primary medical field, one researcher (ML), a general practitioner of Korean medicine working at a primary clinic, also participated in development process. In addition, another researcher (SIY) participated as an expert in psychology to provide advice on mind-body modalities.

The draft of the updated manual was written by HWS and SH. Then, the others independently read and critically reviewed the draft. We held informal meetings twice, and revised the draft to reflect all researchers’ opinion.

2 Narrative Review

A selective literature search method was adopted to examine the latest trends and expert perspectives on mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Among articles published before June 1, 2021, we conducted a keyword search using the terms “COVID-19” and “mental health.” For a rapid review, we limited the search database to MEDLINE (via PubMed), omitting gray literature. The study designs were limited to meta-analyses, reviews, and systematic reviews, to examine only the latest trends and expert knowledge (Supplementary Table 1).

Four researchers (HWS, SH, HWL, and ML) reviewed the titles and abstracts of the searched articles and excluded articles unrelated to COVID-19 and mental health issues. The two researchers (SH and HWL) read the full-text of the article, and excluded articles on topics that were irrelevant to the manual. Then, we classified the selected articles according to their themes. For articles with overlapping themes, we extracted subthemes based on the consensus of the two researchers after selecting articles through discussion.

Next, we selectively searched, selected, and reviewed previous manuals. The materials to review were as follows: 2020 Mind training manual for doctors of Korean medicine at the COVID-19 treatment sites [informally published work], psychological support guideline for the novel coronavirus developed by the National Center for Disaster and Trauma1), and manual for disaster medical support using Korean medicine for disaster survivors35).

3 Development and Endorsement of the Manual

To reflect the latest trends and expert perspectives on mental health, the data extracted from the narrative review were added to the previously developed manual. During the update process, we did not focus on trauma-induced mental disorders such as acute stress disorder and PTSD, which were previously prioritized by other manuals1), but instead focused on emotional symptoms such as anger, depression, and anxiety. Additionally, we aimed to further describe related symptoms, particularly stress responses concomitant with somatization, which do not meet the diagnostic criteria for a mental disorder for which Korean medicine is advantageous. Finally, based on the data collected by the research team, we created an algorithm and manual to improve usability in the primary clinical field of Korean medicine. Thereafter, we submitted our draft to the Society of Korean Medicine Neuropsychiatry for receiving endorsement.

Results

1 Previous Reviews

In the first round, we identified 500 articles. We excluded one duplicate article and 159 articles unrelated to COVID-19 or mental health. Thus, we conducted an initial analysis of 340 articles related to this study’s theme based on content analysis (Figure 1).

In this study, we reviewed three categories: (i) causes of psychiatric problems during the COVID-19 pandemic, (ii) psychiatric symptoms and disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic, and (iii) therapeutic approaches to mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic.

1) Causes of Psychiatric Problems during the COVID-19 Pandemic

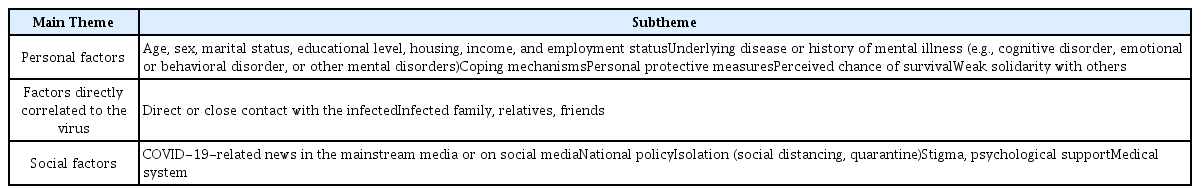

We extracted factors as “causes of psychiatric problems during the COVID-19 pandemic” as follows: personal factors39–41), direct correlation to the virus42–44), and social factors45–48) (Table 1).

“Personal factors” included age, sex, marital status, educational level, housing, income, employment status, underlying diseases, history of mental illness (e.g., cognitive disorders, emotional or behavioral disorders, or other mental disorders), coping mechanisms, personal protective measures, perceived chances of survival, and weak solidarity with others. “Factors directly correlated to the virus” included direct or close contact with infected individuals and infected family members or friends. “Social factors” included COVID-19-related news in mainstream or social media, national policy, isolation (social distancing and quarantine), stigma, psychological support, and medical system. In particular, we were more concerned about children and adolescents, older adults, women (pregnant and postnatal), psychiatric patients with preexisting conditions49–56), people who work at public sites, healthcare workers57–60), day laborers, foreign workers, immigrants, and victims of domestic violence61–65).

Based on these results, we decided to switch classification criteria from quarantine status to vulnerability and risk of symptom severity.

2) Psychiatric Symptoms and Disorders during the COVID-19 Pandemic

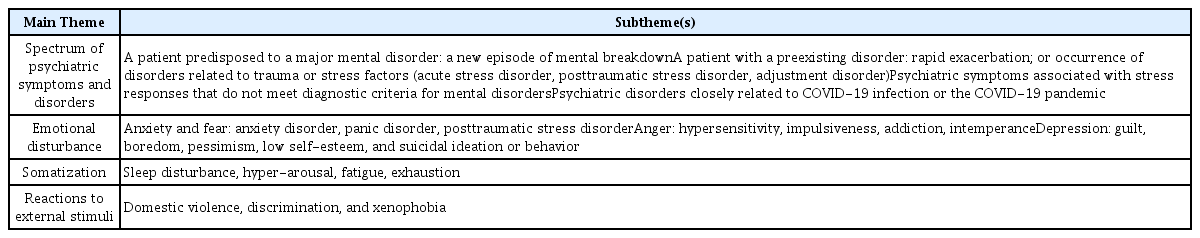

We extracted and categorized the subthemes of “psychiatric symptoms and disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic” as follows: spectrum of psychiatric symptoms and disorders66), emotional disturbance67–71), somatization17,18), and reactions to external stimuli72,73) (Table 2).

As the subthemes of “spectrum of psychiatric symptoms and disorders,” we extracted the following: a new episode of mental breakdown in case of a patient predisposed to major mental disorders, rapid exacerbation in patients with preexisting disorders, occurrence of disorders related to trauma or stress factors (e.g., acute stress disorder, PTSD, and adjustment disorder), and psychiatric symptoms associated with stress responses that do not meet the diagnostic criteria for mental disorders. Psychiatric disorders closely related to COVID-19 infection or the COVID-19 pandemic are as follows: substance use disorder74,75), schizophrenia76), personality disorders77), obsessive compulsive disorder78), PTSD79,80), anxiety disorders81), cognitive disorders (e.g., dementia)82,83), panic disorder84), bipolar disorder85), suicide86,87), eating disorders88), and sleep disturbance89–91). For “emotional disturbance,” subthemes were extracted based on related emotions. We extracted three subthemes regarding anxiety and fear: anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and PTSD. Regarding anger, we extracted subthemes of hypersensitivity, impulsiveness, addiction, and intemperance. Regarding depression, we extracted the following subthemes: guilt, boredom, pessimism, low self-esteem, and suicide. We extracted sleep disturbance, hyperarousal, fatigue, and exhaustion as the subthemes of “somatization.” Domestic violence, discrimination, and xenophobia were extracted as subthemes of “reactions to external stimuli.”

Through this narrative review, we recognized the various aspects of mental problems that the patients and general population experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, we suggested five types that could reflect these findings beyond the major psychiatric disorders: tension (a state of mixed anxiety, anger, and depression), anxiety-dominant, anger-dominant, depression-dominant, and somitization. At the same time, we decided that it is important to have doctors of Korean medicine screen for serious mental illness and to notice them that professional treatment or referral is necessary if suspected.

3) Therapeutic Approaches to Mental Health during the COVID-19 pandemic

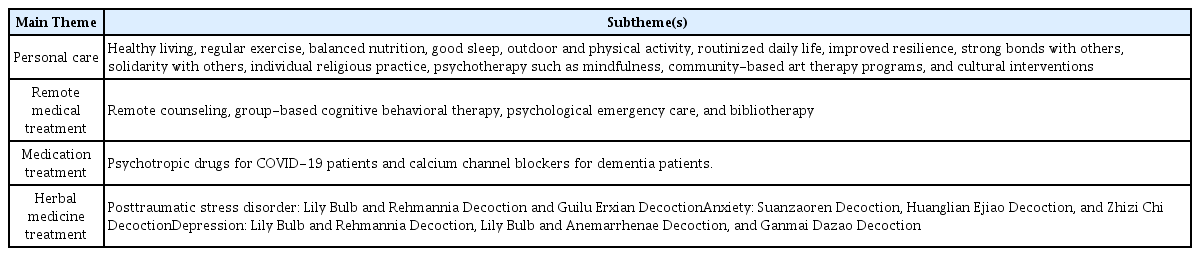

We extracted and categorized the subthemes of “therapeutic approaches to mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic” as follows: personal care92–97), remote medical treatment98–103), medication treatment13–16), and herbal medicine treatment104,105) (Table 3).

The subthemes of “personal care” were healthy living, regular exercise, balanced nutrition, good sleep, outdoor and physical activity, routinized daily life, improved resilience, strong bonds with people, solidarity with others, individual religious practices, psychotherapy such as mindfulness, community-based art therapy programs, and cultural interventions. We identified remote counseling, group-based cognitive behavioral therapy, psychological emergency care, and bibliotherapy as subthemes of “remote medical treatment.” As subthemes of “medication treatment,” we found that psychotropic drugs were used for COVID-19 patients and calcium channel blockers were used for dementia patients. In relation to COVID-19, we concluded that it was impossible to derive evidence-based recommendations for the use of psychotropic medication. We identified the subthemes of “herbal medicine treatment” as follows: the use of Lily bulb and Rehmannia decoction and Guilu Erxian decoction for PTSD; Suanzaoren decoction, Huanglian Ejiao decoction, and Zhizi Chi decoction for anxiety; Lily bulb and Rehmannia decoction, Lily bulb and Anemarrhenae decoction, and Ganmai Dazao decoction for depression.

We were able to confirm that personal care was recommended in addition to remote medical treatment, medication treatment (western medicine), and herbal medicine treatment from the existing evidence.

2. The Previous Manuals for Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic or after a Disaster

We reviewed two previous manuals1,35) and compared the scales for assessment and evaluation.

Both manuals commonly recommended the following scales.

Clinical global impression-severity is only recommended in the psychological support guideline for the novel coronavirus developed by the National Center for Disaster and Trauma1). On the other hand, mental disorder-specific measurements are only addressed in the manual for disaster medical support using Korean medicine for disaster survivors35).

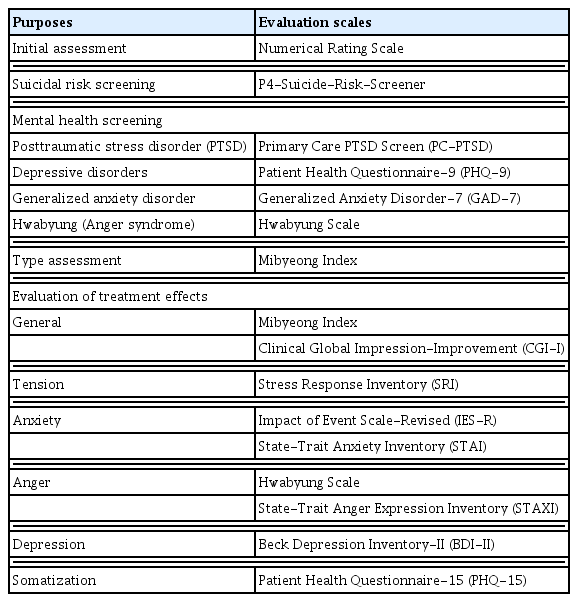

Among these scales, we adopted NRS, P4-Suicide-Risk-Screener, PC-PTSD, PHQ-9, and GAD-7 for essential scales, and adopted clinical global impression-improvement (CGI-I) for re-assessment tools.

3. Field Manual of Korean Medicine for Mental Health Support during the COVID-19 Pandemic

The manual was developed to provide support for medical institutions of Korean medicine (e.g., Korean medicine clinics, Korean medicine hospitals, and public medical institutions) to assess and categorize patients experiencing psychiatric or mental health problems during the epidemic period of infectious diseases such as COVID-19. This manual can be applied to the general population, healthcare workers, close contacts, confirmed patients, fully recovered patients, friends, and families.

The manual consists of three big steps and eight small steps. Small steps are formed as follows: Initial Assessment, Vulnerable Group Screening, Suicidal Risk Screening, Mental Health Screening, Type Assessment, Korean Medicine Interventions for Symptoms, Self-management and Evaluation of Treatment Effects. The first big step is a process to identify at-risk patients, diagnose high-risk groups and transfer them to specialists. First big steps consist of Initial Assessment, Vulnerable Group Screening and Suicidal Risk Screening. Second big step is a process for diagnosing mental illness. If the patient is better diagnosed with a mental illness, it is more effective to follow the previously developed manual for mental illness rather than this Manual. This step consists of Mental Health Screening. Last big step consists Type Assessment, Korean Medicine Interventions for Symptoms, Self-management and Evaluation of Treatment Effects. This step is to properly classify according to necessary treatments and treat the patient.

Figure 2 presents overview of development of the manual. Figure 3 presents an overview of the clinical pathways involved. The key recommendations for mental health evaluation are summarized in Table 4.

Treatment plan flowchart for psychiatric symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic

CGI-I: Clinical global impression-improvement; GAD-7: Generalized anxiety disorder-7; MBI: Mibyeong index; NRS: Numerical rating scale; PC-PTSD: Primary care posttraumatic stress disorder screen; PHQ-9: Patient health questionnaire-9; PMR: Progressive muscle relaxation

1) Initial Assessment

For the patients’ initial assessment, NRS was used for rapid risk evaluation. The level of pain experienced by the patient was expressed on a scale of 0–10, with 10 indicating unbearable pain and 0 indicating no pain. A score of 4 or below with no significant functional abnormalities was considered to indicate low risk. A score of 5 or higher affecting the functionality is considered moderate to high risk, which requires medical intervention. Emergency psychiatric screening was recommended when necessary. A neuropsychiatric referral should be made when a patient is deemed emergency patient120).

2) Vulnerable Group Screening

Even low-risk patients should be screened to determine vulnerability. When a patient is found to be susceptible, they can be classified as moderate-to-high risk and given a treatment suitable for the moderate-to-high risk group at the doctor’s discretion, even if the patient’s case is normal or mild.

(1) Low Risk of Severity

While some patients reporting neuropsychiatric symptoms due to the impact of COVID-19 require formal neuropsychiatric treatment, most people benefit from supportive interventions (e.g., mental health education and relaxation therapy) to improve health or resilience to stress. For patients experiencing normal-to-mild neuropsychiatric symptoms, it is possible to stabilize them by providing them with mental health education and by explaining that their neuropsychological symptoms are common responses to an infectious disease pandemic and that human beings have the ability to respond to stress in even more severe situations121). Additionally, doctors of Korean medicine, as well as social and mental health services, can introduce a method of managing and coping with stress (e.g., healthy lifestyle, routinized daily life, solidarity with others, and psychological therapy such as mindfulness)92–97). When necessary, a doctor can advise patients to seek professional assistance. For self-care, doctors can utilize relaxation therapy, which includes breathing techniques, mindful breathing, and walking meditation120).

(2) Moderate-High Risk of Severity

Even among patients with normal-to-mild psychiatric symptoms, individual resilience is reduced if stress factors persist, making it difficult for them to return to normal daily life. Ongoing stress exacerbates existing psychiatric or psychological problems among vulnerable individuals, and can cause new psychiatric symptoms among healthy individuals. Persistent fear caused by COVID-19 and a lack of belief that the pandemic will be resolved can lead to anxiety, depression, and anger. Continuous tension induced by the external environment can perpetuate and solidify temporary somatic symptoms such as sleep disturbance and fatigue. These symptoms require management through appropriate interventions and mental relaxation 121). Groups that are more vulnerable to pandemic-related psychosocial stressors include people with illnesses, risk factors (children/adolescents, older adults, women, and people in regular contact with the public), preexisting psychiatric issues, and healthcare workers49–60). For the general population, if psychiatric symptoms are severe or persist for an extended period, doctors can utilize medication13–16), herbal medicine104,105), supportive counseling, and psychotherapy (e.g., remotely conducted mind-body intervention and problem-solving strategy)98–103). It is essential to consider vulnerable patients during treatment and apply a multidisciplinary approach, depending on disease severity and comorbidity121).

3) Suicidal Risk Screening

The P4-Suicide-Risk-Screener106) was used to screen psychiatric emergency situations, such as suicide risk and self-harm.

4) Mental Health Screening

The following screening tools can be used to screen for significant mental conditions: PC-PTSD107), PHQ-9108–111), GAD-7112–114), and Hwabyung scale122). Critical cases such as trauma-induced mental disorders (acute stress disorder and PTSD), cognitive disorders, and psychiatric disorders should be categorized separately as significant mental conditions and addressed using traditional treatments. These cases require appropriate treatment in accordance with the previously developed clinical practice guidelines for Korean medicine.

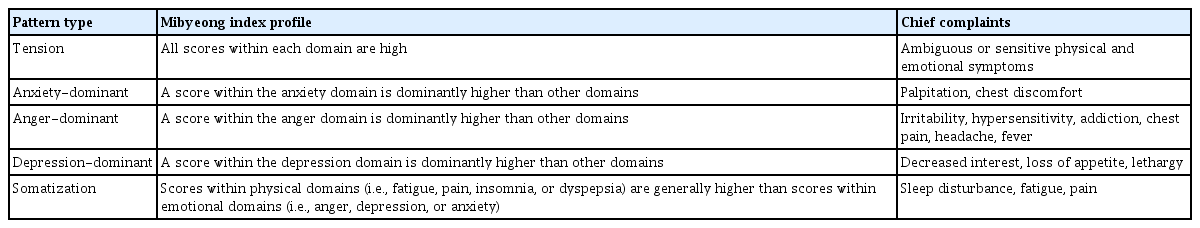

5) Type Assessment

The COVID-19 pandemic has persisted for over two years and has shown long-term effects. To provide a suitable self-care guide, doctors of Korean medicine should categorize patients into the following groups: tension, anxiety-dominant, anger-dominant, depression-dominant, and somatization (Table 5).

The Mibyeong index (MBI) is used to classify the types. The MBI was designed to assess the health status of healthy and subclinical populations123). This instrument measures the severity, duration, and resilience of physical symptoms such as fatigue, pain, sleep disturbance, indigestion, and mental distress, including anxiety, anger, and depression.

Tension types may report ambiguous or sensitive physical or emotional symptoms. Other types of patients may also report specific symptoms. For example, the anxiety-dominant type is related to palpitations and chest discomfort; the anger-dominant type is related to irritability, hypersensitivity, addiction, chest pain, headache, and fever; the depression-dominant type is related to decreased interest, loss of appetite, lethargy; and the somatization type is related to physical symptoms (e.g., sleep disturbance, fatigue, and pain).

6) Korean Medicine Interventions for Symptoms

When a significant disorder is present, the patient is treated using existing traditional treatment. When a clear diagnosis cannot be made, despite the presence of various psychological and physical symptoms, treatment should focus on the most dominant symptom.

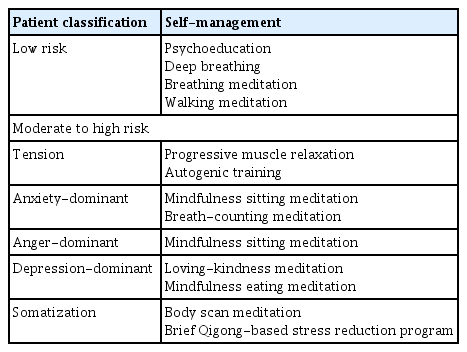

7) Self-management

For patients who visit medical institutions of Korean medicine, self-management methods such as relaxation and meditation can be taught for each symptom (Table 6).

The relaxation method is a part of the mind-body intervention method and refers to a technique for reducing physiological and psychological stress. Relaxation methods include deep breathing, breathing exercises, progressive muscle relaxation, autogenic training, relaxation using biofeedback, guided imagery, and self-hypnosis. Meditation is a well-established oriental practice that assists in the management of psychological symptoms, such as depression, anger, anxiety, and fear. While a therapist can perform meditation with a patient, it has the advantage that the patient can do so on his or her own after learning the technique. Meditation techniques vary, but one common goal is to relax the body, realize the suppressed self, and awaken senses while focusing on breathing. Using this technique, patients can experience the effects of physical relaxation, emotional control, and sedation. The principles and methods of autogenic training, relaxation exercises, and Qigong’s breathing technique are similar to those of meditation. Recently, an MBSR program was developed based on mindfulness, which is the core principle of Vipassanā or meditation120).

8) Evaluation of Treatment Effects

At the patient’s follow-up visit, the NRS was used again to check the level of improvement. For a more precise evaluation, MBI and CGI-I can be used. The validated scales for measuring symptom severity are summarized in Table 4.

4. Endorsement

The Society of Korean Medicine Neuropsychiatry operates a clinical practice guideline review committee. The committee reviews and endorses not only evidence-based clinical treatment guidelines but also manuals that can be used in the field. The committee consists of a total of 6 members, separate from the society’s executives, and each member independently reviews the submitted clinical guidelines or manuals based on the society’s criteria and decides whether to endorse or not through a meeting.

The criteria of the Society are as follows.

Is this guideline (manual) consistent with the purpose and direction of the society?

Has this guideline (manual) systematically reviewed the available evidence?

Are the guidelines presented in this guideline (manual) clearly described?

Did the guide presented in this guideline (manual) take the user’s point of view into consideration?

Are the guidelines presented in this guideline (manual) suitable for application to the target patient?

Will the benefits outweigh the harm to the patient if these guidelines (manuals) are followed?

After the society’s review, we received an endorsement from the Society of Korean Medicine Neuropsychiatry on June 30, 2022.

Discussion

Although the COVID-19 pandemic has induced many types of neuropsychological distress, no definitive evidence-based manuals have been identified for these symptoms and illnesses. Psychiatric symptoms (e.g., depression, anxiety, anger, sleep disturbance, and stress disorder) are predictable symptoms that can develop when an infectious disease spreads or social distancing or lockdown is implemented10). The most important approach during a pandemic is the psychological approach, not the medication approach; thus, the use of medication should be minimized124,125). Thus, this manual was developed out of urgency for guidelines to promote self-management in patients visiting medical institutions of Korean medicine who report neuropsychological symptoms related to the COVID-19 pandemic. To update the manual, we conducted narrative reviews and reached informal consensus. Based on these results, we submitted the draft of this manual, and received endorsement of the Society of Korean Medicine Neuropsychiatry.

From the aforementioned perspective, this manual emphasizes psychological education, mind-body intervention, and psychotherapy in the treatment approach. The strength of Korean medicine is that it provides both preventive measures and mind-body interventions. This manual aims to screen low-risk patients through risk assessment, so that doctors of Korean medicine can boost individual patients’ resilience by focusing on psychological health education and self-management methods to understand and manage their symptoms, even without direct medical intervention that utilizes medication or psychotherapy. In the meantime, vulnerable groups are screened so that doctors of Korean medicine can provide suitable treatments and interventions for low-risk patients who require help. Therefore, this manual systematically classifies participants and respects the self-recovery of individual patients. Psychological training and self-management methods were highlighted for patients who did not require medication or in-depth psychotherapy. For moderate-high-risk patients who required treatment, we aimed to implement adequate management and necessary treatment. For appropriate self-management, we suggested classification of the patient’s type by referring to the scales as follows: tension, anxiety-dominant, anger-dominant, depression-dominant, and somatization.

The manual for disaster medical support using Korean medicine for disaster survivors is already developed and published for disaster survivors35). The Manual for Disaster survivors gives understanding of PTSD and suggest various psychological treatment methods such as Stabilization Programs, Emotional Freedom Techniques. However, there are more psychological symptoms caused by COVID-19 than PTSD, and most general Korean Medicine doctors are not familiar with those psychological treatment methods. Most of psychological symptoms caused by COVID-19 are not serious as disaster survivors’ PTSD symptoms and most of patients have power and resilience to overcome such obstacles. So intensive psychotherapy suggested by Manual for Disaster survivors might not be effective if the techniques conducted by unprepared therapists with mild psychological symptoms under the circumstances of COVID-19. Rather self-management techniques such as meditation is more useful for patients with mild symptoms which most patients are126) and meditations are more familiar and can be easily reached and practiced by patients and doctors by Internet or YouTube. Therefor doctors on the front lines facing the problem, it is important to identify at-risk patients and diagnose high-risk groups. Quickly identify at-risk patients and high-risk groups, and have experts apply the developed disaster manual or other manual for mental disorders. For those who are not serious psychological support, conventional Korean Medicine intervention and meditation techniques are sufficient126).

The strengths of this study is that the manual provides a clinical pathway and this manual is developed with a focus on primary medical care where patients come with mental pain caused by the COVID-19 outbreak rather than disaster sites to increase the usability of the manual. In addition, we tried to consider situation of primary practice and experts’ experiences and through literature search, additional considerations in the clinical field were reinforced through the research of other clinical experts. Finally, this manual is developed for a specific disaster situation ‘COVID-19’. Disasters such as epidemics of infectious diseases have different characteristics from general disasters such as natural disasters, war, terror, and accidents. Epidemic disasters are continuously increasing, and this manual contains the concept of epidemic disasters and can be referred to disasters caused by other epidemic diseases that will occur in the future.

However, this study had several limitations. First, this manual was developed by a small research team at the KMMH center based on the narrative review. This is not developed by evidence-based methodologies but by informal consensus development methods. More rigorous methodological reinforcement and a formal consensus process (e.g., focused group interview, Delphi methods, or opening of public hearing) is required. Second, this manual has not been empirically tested. We need to collect and report a case or case series compliant with this manual and conduct clinical research to investigate the contents of the manual. Lastly, we did not include much information about herbal medicine and acupuncture, and focused on self-management in the manual. As mentioned above, we emphasize psychological education, mind-body intervention, and psychotherapy over herbal medicine and acupuncture for a stressful population during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusion

This manual suggests several clinical implications. Firstly, psychological complaints of patients during the pandemic need to be preferentially considered as natural responses or phenomena rather than major psychiatric disorders. Thus, we suggested risk screening for all patients in order to manage the patients regarding their severity. If necessary, practitioners have to treat the patients as mental disorders or referral the patients to higher-level medical institutions. For this, this manual suggests essential scales which can be easily used in primary clinics. Secondly, doctors of Korean medicine should systematically classify patients who visit primary care institutions based on the patterns of the symptoms as follows: tension, anxiety-dominant, anger-dominant, depression-dominant, and somatization. Self-management also had better to be delivered individually according to patients’ status. This manual would help doctors of Korean medicine decide the type of self-management modalities for the patients. Finally, in doing so, we expect the use of this manual in Korean medicine as well as in other primary care institutions, public health centers, and local health centers.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1.

Search terms

Acknowledgements

None

Notes

Financial support

This work was supported by a grant from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HF20C0079).

Data availability

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary materials, and further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethical statement

No ethics approval was needed.